July 28, 2025

(This post is part of the Into the Wild series. Visit the Into the Wild introductory post to learn why I’m sharing this.)

Last summer, I felt drawn to visit my childhood home in a rural part of central Texas. I had been working with a coach who introduced me to a type of self-therapy known as “parts work” which is based on the theory that we are not just one person, but instead our psyche is made up of numerous sub-personalities, or parts, that work together within a system. Developed by Richard C. Schwartz, PhD and also known as Internal Family Systems or IFS, working with our parts involves imaginative and meditative interactions, often with younger versions of ourselves. I had been doing weekly IFS sessions with my coach for almost six months and some of my sessions gravitated toward times when I was living in this house, so I wanted to go stand in the very place where my ego was first active within me. My curiosity was simply wondering how it would feel and if I’d remember or discover something new about myself by standing on what I considered hallowed ground.

I lived in this house from birth to around age seven, and then spent many summers there when I visited my dad after my parents divorced. My dad still owns the place, but hasn’t lived there in decades. It’s the third house at the end of a dirt road – my grandparents lived in the first house until they passed on, and the second house had been my great-grandparents’ house before, but is now occupied by my aunt and uncle. I have so many memories of playing with my sister in the creek that ran behind the houses, but today the creek is dry.

My Uncle Randy offered to drive me over on his Mule ATV since the land is overgrown with tall grass, new trees, and other foliage. More memories floated into my mind gently and fondly as the wind lifted my hair off of my shoulders. As we approached the dilapidated house, I noticed a giant hole in the roof just over my parents’ old bedroom. As soon as we stopped the vehicle, two turkey vultures emerged from the hole and sat on the roof.

Sadness dropped into my stomach as I took in the scene of what – in my mind – used to be a place so full of life.

I took a photo and went inside the house. Almost every detail of that place – the size of the hallways, the placement of the full length mirror on the wall, the color of the orange rotary phone with the longest cord ever, and the way the afternoon sunlight shone through the windows was already engraved in my mind. But the house was abandoned and neglected for the last 30 or more years, so it was dirty, damaged, and in disarray.

I turned right down the hallway towards the bedrooms. The door to my parents’ bedroom was closed. I decided not to go in there, mostly out of fear that a vulture would chase me out, and I entered the room I shared with my sister instead. I took another photo.

I didn’t stay inside long, but as I looked around, I felt a sense of deep connection to this house. It was sad to see it in the present – juxtaposed to my crisp memories of the past – but I accepted the changes and stepped back outside in the front yard.

My uncle was still sitting in the ATV when I spotted a large animal skull in the grass. It looked like a sheep with big curved horns. I picked it up and smiled as I showed him what I found.

“That’s an Aoudad.”

He responded without surprise even though Aoudad’s are not native to Texas. They are imported from North Africa for trophy hunting. He explained that a few eventually became wild in this area after escaping the hunting leases.

I decided to take it home with me, not really sure what I was going to do with it.

When I got back to the city, I put it on my front porch next to some potted plants, and few days later, while sitting there enjoying the sunshine and the sounds of the birds, I inspected it closely. I ran my fingers along the smooth surface of the face and traced around the eye sockets and up and down along the curve of one horn. The horns’ texture was rough and bumpy. I imagined it used to have a smoother casing around the bone to make for a prettier horn.

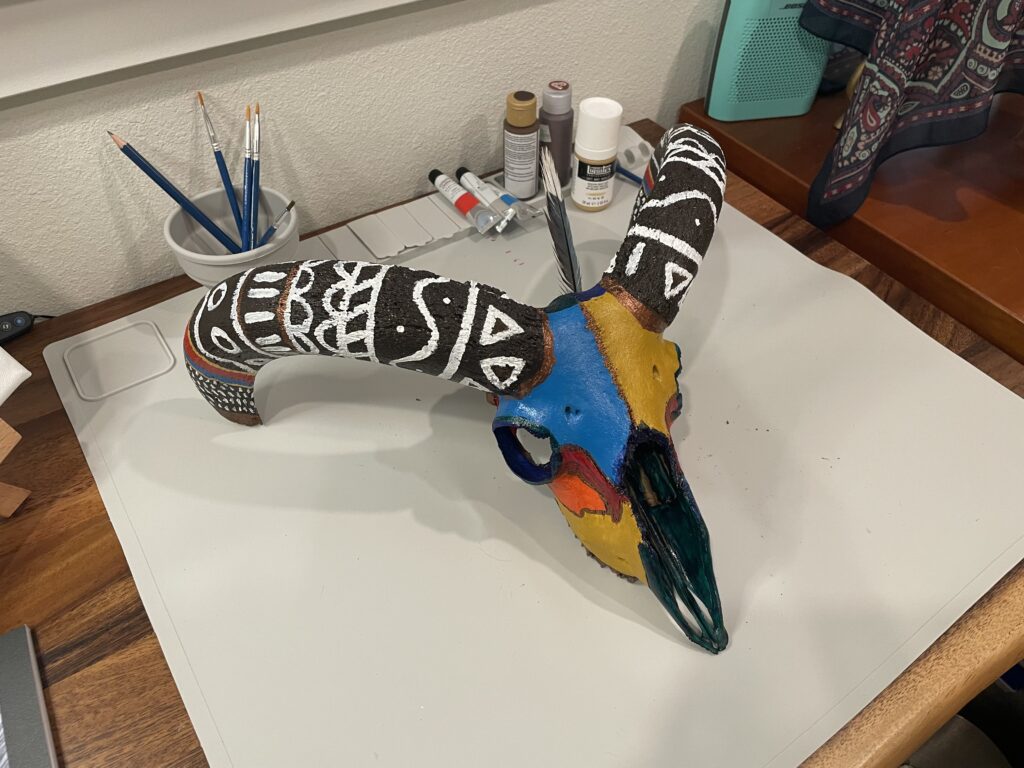

It was in this moment I decided to paint the skull. I spent some time cleaning it up with vinegar and a brush before laying down some colors. I didn’t have a plan, and reminded myself that if I didn’t like what it looked like, I could paint over it with a different color. As I brushed the paint over the bones, I imagined geometric shapes and lots of colors. A tribal image was forming in my mind and I wanted to do my best to transfer it from my thoughts to my unique canvas of bone.

I worked on the piece for hours and hours over the course of more than a month. When I felt inspired to revisit it, I’d add another color and more detail to the edges. At one stage, I covered the horns with tape to make them smooth instead of bumpy. I wrapped them with the only tape I had – electrical tape. Only after both horns were completely wrapped in black tape and I had started painting the face, could I see that my paint wasn’t going to look good over that tape. I eventually stripped it back off and that’s where my geometric shapes started coming in.

I painted, I found feathers on walks and added them to the design, and I felt a connection with this Aoudad. I learned a little bit about the animal in it’s natural habitat. I began to see that symbolically, this skull represented one of my parts – it’s a part of my psyche I call the Survivor.

Pause and Reflect

Before I tell you what this skull came to mean for me, I want to invite you into a moment of your own reflection:

- What part of you has kept you alive through hard things?

- What part made you strong when you needed to be – even if it wasn’t sustainable forever?

- What does your Survivor look like?

Meet the Survivor

Aoudad, or Barbary sheep, are native to North Africa and are known for their resilience, adaptability, and ability to thrive in harsh, desolate environments. They are extraordinary because of their ability to live in extreme conditions with rocky, unforgiving terrains and limited resources.

Among the indigenous people of North Africa, the Aoudad represents resilience and resourcefulness. These animals are the essence of survival in harmony with challenging landscapes. Where domesticated sheep are generally representative of compliance and docility, the Aoudad is quite the opposite. These ingenious creatures symbolize untamed strength and independence.

And there’s a part of me that identifies strongly with the characteristics of this animal.

My guess is that you have a part like this, too.

That part of us that finds a way when there seems like none exists. That part that learned to make what we have enough. The part of us who drives a lot of our success and achievements.

I’ll be sharing more about my personal story in future posts, but for now it’ll suffice to say that my path has not been an easy one, particularly because when I realized I was romantically attracted to girls instead of boys at age 16, and was deep in the Christian faith, both internally and externally. I lived more than 20 years absorbed in a duality and dissonance that spurred me to wrestle with God and with myself, and keeping my external world together – surviving – became my number one mission.

I became the essence of survival in harmony with challenging landscapes, too.

The Survivor, the Aoudad sheep, the part of me that gave me the strength to succeed against all odds holds a special place in my heart. I feel compassion and gratitude for this part of me because I know, without it, I could have easily ended up living a completely different life having given up somewhere along the way.

All of the parts of our psyche have our best interest in mind. The trouble is that some parts are immature and react from that immaturity with old tactics that often need to be retired or upgraded to something more suitable for our present time.

Like anything to an extreme, letting this part rule my life for so many years took its toll on me. The Survivor found a tactic that worked when I was younger and just kept driving me to work harder. Living in survival mode kept my body tense and my nervous system in the sympathetic (fight or flight) state. This level of alertness was unsustainable and I eventually found my burnout boiling point.

The Survivor has served me well for decades, and painting it’s wildness was like shining a light on this part within me. I was finally seeing how this hardworking part deserved my thanks and also needed to develop an upgraded tactic for keeping me safe. I am safe now – physically safe from harm, financially secure, and emotionally stabilized.

It is time to move from surviving to thriving.

It is time to embody other parts of my psyche, too.

Just when I thought The Survivor had given me all it came to give, two more skulls arrived. When my dad saw my finished painting of the Aoudad, he connected with a friend who works on an exotic animal ranch. That’s when I was gifted the skulls of a goat and a 9-point (antlered) deer.

I didn’t know it then, but I was being invited to meet the next part of myself. The one who leaves the well-worn path. The one who takes risks. The one who is not content to simply endure, but longs to expand.

That part of me? She’s The Explorer.

I’ll introduce you next week.

For the video series, subscribe to my YouTube channel to join the journey, Into the Wild.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Get Weekly ReCaps of My Spring Equinox Experiment

Last year, I completed a project called 100 Liminal Days that changed my life and showed me the power of time-bound experimentation.

Now, from January 26, 2026 - March 16, 2026 (50 days), I'm working to build a sustainable restorative habit of cooking meals mindfully instead of eating so much takeout and pre-made meals in single-use containers. You can learn more about the project here. Check out the book that inspired the project, Meaningful Minimalism for inspo for your own exploration!

In my weekly newsletter, I will share updates on the experiment (like these!), short beginner-level qigong practice videos (like these!), and stories behind my art (like these!)

Sign up below to receive weekly updates and I'll send you this free Notion habit tracker template I created to elevate self awareness and journal about the day.